Just The Axe Ma'am #14.5 - Eleven Questions of DOOM! With Graham Thomas Wilcox.

Interviews with authors of New and Notable Sword & Sorcery

Welcome to the second installment of our companion feature to our monthly newsletter, Just The Axe, Ma’am!

Graham Thomas Wilcox has been crafting Sword & Sorcery and Dark Fantasy-themed short fiction, with “Lord of Slaughter” first appearing in issue five of Whetstone Magazine. More recently, he launched Old Moon Quarterly in 2022, a magazine devoted to Sword & Sorcery and Dark Fantasy “in the tradition of Clark Ashton Smith, Karl Edward Wagner, and Tanith Lee.”

Two more stories have appeared there:”Stella Splendens” in issue 1 (which you also can read online here), and “The Feast of Saint Ottmer” in issue 3,

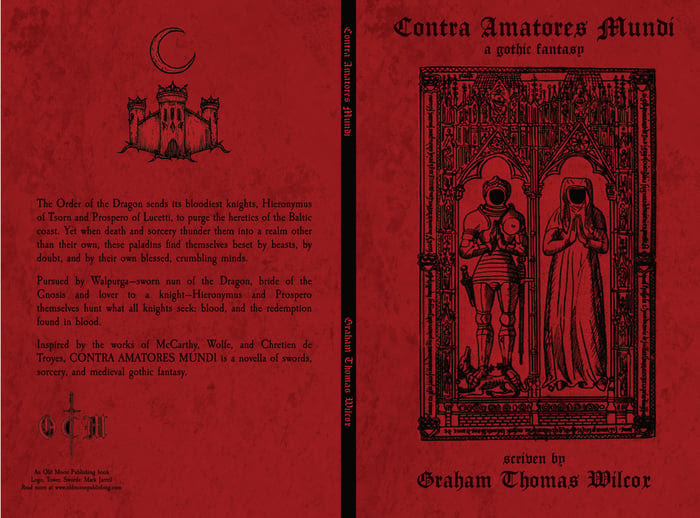

Now, he is about to release his first novella, Contra Amatores Mundi, which is due for release this Halloween, so we figured it was time for him to face The Eleven Questions… of DOOM!

1. What was the work that made you fall in love with reading? What was the work that made you fall in love with writing? What work made you fall in love with Sword & Sorcery?

Hm, it’s hard for me to remember! I think it’s probably Brian Jacques’ Redwall, which I read when I was very young. It helped that PBS had a cartoon for the series, too, I’m sure. Jacques described these sumptuous feasts the little animal people had in their abbey, and I distinctly recall asking my mom to help me find recipes online so we could make “mallowcream” or something like that.

But the first work I can remember really diving into and exploring as a serious reader, so to speak, was J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. My parents had a very nice set of the three volumes, and I read them until they (literally) fell apart. I think I checked out the Silmarillion from the library so many times I might as well have owned it.

The work that made me fall in love with writing, however? I can’t point to any particular story. But it probably had something to do with Warhammer 40,000, the miniature game. My older brother had all the first-edition and second-edition rulebooks, with that crazy John Blanche art and these little vignettes scattered throughout, and I loved the weird, gothic nature of the setting, even as a little kid

The first things I ever wrote were little backstories for my armies in that game. I remember combing over message boards back in the day, reading other people’s fan fiction and feverishly typing my own on my home computer. I was a big fan of Space Marines (still am!) and probably wasted many an hour creating (very derivative) “homebrew” Chapters.

As for sword and sorcery, I came to the genre somewhat sideways, I think. In high school, I played the online RPG Age of Conan—a very fun, albeit imbalanced, game. And you’d think that got me to read the original Conan stories—that would have been the sensible route. But nay. On their message boards (a theme emerges), I saw someone recommend a fantasy trilogy called The First Law, written by some British fellow named Joe Abercrombie. They said it had a really cool and interesting depiction of a berserker-type character. That intrigued me (I played Blood Angels in 40k, and so always loved a good berserker). I read that series and loved it. In particular, I loved the focus on smaller stakes (or so it seemed to me), and on decidedly mercenary characters who desire rather grounded things—” let me live through this next battle,” “let me gamble some money and maybe get a girlfriend,” “let me get revenge on those who wronged me.”

Abercrombie’s frank engagement with violence and how it might seduce someone intrigued me as well—I was used to seeing “berserker” characters as some variation of “that big guy who hits stuff hard but has a heart of gold” or “flawed paladin,” and so his character Logen Ninefingers, who has a pretty realistic (and tragic) relationship to his anger, felt new and exciting to me.

So, I started seeking out similar works. That led me, in a roundabout fashion, back to Robert E. Howard and his ilk.

2. You have written for the Warhammer setting for Grimnirsson (The Warhammer Age of Sigmar, to be specific). What appeals to you about the setting?

I’ve written a couple more stories now too, actually. Hopefully, they will release it within the near future. I started writing for Age of Sigmar because I was (and am) a big fan of Warhammer’s “Old World” setting. I inherited this taste from my older brother, as I mentioned above. I won’t dive into all the complexities of the setting itself, nor its history (Games Workshop destroyed the “Old World” setting, then resurrected it; Age of Sigmar was originally a replacement/vague continuation of that destroyed setting—it’s now its own thing), but suffice to say, I loved the gothic aesthetic and the historical settings which inspired the Old World. I loved how “low fantasy” the Old World could be as well—in the roleplaying game associated with the setting, you didn’t necessarily play the shining knights and dimension-hopping wizards of Dungeons and Dragons. You played a rat catcher with his “small, but vicious, dog,” or a bug-eyed witch hunter—or perhaps a drunken, ginger dwarf with crippling shame and a fondness for axes. That felt very different to me, in a good way. I liked the grubbiness of it, I think, and the wry irony attached to the setting. A lot of that has filtered down into other RPGs now if I’m not mistaken. But I first encountered it in Warhammer.

Age of Sigmar is a bit more “high fantasy” than the Old World. But in a way, it’s a bit freer, too. In the Old World, the various cultures are pretty well set: you have the Arthurian/Monty Python-esque Bretonnians here, the Renaissance-Germans- but-steampunk Empire here, the heavy metal daemon-worshipping Swedes up here, and so on. Age of Sigmar takes place in these sorts of ever-expanding, ever-shifting magical realms, very much inspired (in some small fashion) by the nine realms of early medieval Scandinavian myth, and they are populated by cultures which range from the historically inspired to the utterly fantastic. This provides an author with some more latitude, so to speak. You can take an idea and really run with it. There’s still a canon to which you must adhere, as is often the case with licensed fiction, but you can bring in some stranger ideas on occasion—ones that wouldn’t fit in the Old World—and give them life in Age of Sigmar.

3. Most of your original fiction is actively set in medieval times. How do you use that to capture the mindset of characters from that era?

It’s tricky. I love literature that explores a particular mindset and grants me some sort of insight into a worldview other than my own. I’m thinking of Gene Wolfe’s Soldier of the Mist and Book of the New Sun, or Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and Outer Dark—or medieval works of literature themselves, of course, such as Tirant lo Blanc or Perlesvaus. The characters in these works value moralities other than my own—they understand “truth” differently, perhaps, or see something fantastic in what I consider the mundane, and vice versa. Yet, despite all these differences, they speak to something else, too: some common ground. I hesitate to name it a universal theme or idea (like Ockham, I am not sure where I fall on the concept of universals). Regardless, the tension between these differences and these commonalities appeals to me. So, I try to replicate it in my own work.

For me, that means researching and attempting to understand those works that contributed to the worldviews and mindsets of people from a particular time and place. I think it’s pretty common to read works ostensibly set in a medieval, or medievalesque, world wherein the characters think and act more or less exactly like modern English-speaking people from America, Canada or the UK. That’s fine, but I find myself more intrigued by works that attempt something different. Medieval Europeans weren’t utterly alien—we’re their cultural descendants, after all. But they grappled with material circumstances, theological concerns, and philosophical quandaries other than those affecting our modern world. So I try and read some of the works I think my characters might have read—the chivalric romances, the philosophical tracts, the theological debates—and construct what I think might be a relevant worldview. I don’t make any claims towards historical accuracy—anyone familiar with medieval Europe who reads my work will see where I diverge from history right away—but I do think this research, this immersion (so to speak) in the cultural milieu of a past age, informs my writing and lends it a particular flavor.

4. What is the most important lesson you’ve learned as an author?

Hard to say. Getting comfortable with rejection, I suppose. You’ll face a lot of it as a writer, and it stings. It can be tempting to take these rejections personally.

Publishing is just about the same as any business anywhere: it isn’t set up to be fair. Something easy to acknowledge in the abstract. But when you start seeing how the industry is unfair to you or to people you care about, it can sadden you. Or anger you. It can make you want to give up writing in general. I’ve been there; perhaps I’ll be there again, too. So, cultivating a sense of resilience to rejection and all its attendant difficulties is important. I’m fairly self-critical, and when I read a rejection, it can feel like it’s a validation of what I already “knew” about my work and its worth. A venomous mindset at times, sadly, and not uncommon among the authors I know.

Some authors I know gamify the rejection itself—they write and submit and write and submit and compete to receive the most rejections in a year. I think that’s a helpful way of looking at it—biting one’s thumb at the entire idea of rejection, in a way. Having someone on your side helps a lot, too—Caitlyn, my wife, reads my work and gives me excellent critiques. But she also let me know she loves my work. Julian, the publisher of Old Moon and my very great friend, does the same. Having even one or two sympathetic voices can do wonders. Without that support, I do not know if I would still write.

5. We find inspiration everywhere. What is a favourite painting, a favourite song, a favourite film?

Favorite painting: perhaps The Triumph of Death by Pieter Brughel. I love Renaissance art in general, and this one nails a sombre note I find compelling. Dürer’s Knight, Death, and the Devil is an engraving rather than a painting, but it is certainly my favorite work of art.

Favourite song: A difficult choice. I listen to a lot of black metal. If I can cheat, let me name a favorite album: Litourgiya by Batushka.

Favorite film: Also tough! The Big Lebowski, probably.

6. As well as being an author, you are an editor of Old Moon Quarterly. What goals have you set and hope to achieve for the magazine?

We want to keep publishing the sort of stories we want to read—hopefully, others want to read them too! We’d love to publish some themed issues in the future. I am personally a big fan of Arthuriana (big surprise, I know). Perhaps an Arthurian issue in the future, then. I know we (Caitlyn, Julian, and I) want more illustrations in later issues as well. If we could somehow convince John Blanche or Ian Miller to work with us, that would be very metal.

7. The First Wave of Sword & Sorcery is when it was formed in Weird Tales of the 1930s. The Second Wave is when it rose high from the 1960s to the 1980s. The Third Wave is now. What is one work from each wave you want everyone to read?

From the First Wave, I think everyone should read Robert E. Howard’s “The Shadow Kingdom.” Kull is one of his most interesting characters; he radiates an aura of doom and tragedy that appeals to me. He is a conflicted man—far more so than Conan, Turlough Dubh, or most of Howard’s other characters. Howard abandoned the character because he felt Kull’s psychological tension was inauthentic. I think that’s a shame.

From the second wave, I’ll offer two: Nifft the Lean by Michael Shea, and Soldier of the Mist by Gene Wolfe. The first is unabashedly sword and sorcery, written in beautiful and verbose prose that recalls (and surpasses, in my estimation) Jack Vance. The second is, I would argue, also sword and sorcery (I’m quite certain it matches all of Brian Murphy’s criteria, for example) but it is filtered through Wolfe’s unique literary lens. Purists might disdain its inclusion under the wider generic tent.

Regardless, I wrote about the worldview in a prior question. Soldier of the Mist captures an antiquated worldview better than almost any modern work I’ve read.

It’s worth it for that alone. Wolfe’s prose is beautiful as well, albeit more restrained than Shea's. To me, both works encapsulate what sword and sorcery can be—how far we can warp the genre while still maintaining its essential timbre.

From the Third Wave, I’d say Howard Andrew Jones’s Hanuvar cycle or James Enge’s Morlock stories. Both are excellent authors, albeit in different ways. Jones writes true heroism in a manner that reaches beyond the platitudes we sometimes see. Enge’s irony, humor, and Laconic prose are unmatched. “The Second Death of Hanuvar” is a great intro to Jones’s character; “The Singing Spear” was my first Morlock tale and one which I still love.

8. You have a novella coming up this Halloween. What does it promise to the reader?

Yep, Contra Amatores Mundi. I think I’ve pitched it as “Gene Wolfe, Cormac McCarthy, and Chretien de Troyes play Dark Souls.” That’s a bit flippant, but I think it captures my aims. The characters are weird, the prose is stylized, and the tone is dark. On one hand, it’s a story about men in armor hitting stuff with swords for personal reasons—very much a sword and sorcery tale in that sense.

On the other hand, well, it’s about some other stuff too. Hopefully, that other stuff doesn’t get in the way too much. I won’t bore you all by talking too much about it.

If you read the novella, I think you’ll get the picture.

But if you’d like some insight into what inspired the story, here you go. If you like to read chivalric romances (words you write once you’ve accepted a niche audience), you’ll notice that one of the questions that pops up over and over again is, “Why would you want to be a knight?”

Sometimes, this question is explicit. Other times, it’s implicit. Often, we see it paired with “What does it mean to be a knight?” Or even “Can you be a man if you’re not a knight?” Other questions abound as well. The chivalric romances of the period answer these myriad questions in different ways. Some rather complex and interesting ways, in fact! I won’t (and let’s be honest, could not) summarize all of our modern scholarship on the ideology of chivalry and how it affected the men who practiced it. Suffice it to say, some of them (possibly many or most of them) had a view of the world and of violence, which seems pretty alien to most modern sensibilities. In short, knights really loved violence and valorized it. They thought it was pretty central to their “worthiness” as men. But they weren’t a monolith, either—we see self-critical reflections on the topic appear, too.

So, I think it’s fun to imagine what someone raised on those stories—someone who is, in every way possible, their intended audience—might think or do. But I also really like late antique Platonism and early Christian gnosticism; I don’t believe in them, but Plotinus would surely have written a killer RPG splatbook (Valentinus too, for that matter). I am also very fond of early modern English verse, particularly Paradise Lost. So that all gets thrown in there, too

Ultimately, if you like the weird and gothic aesthetic of games like Dark Souls or books like Between Two Fires, I think (I hope) you’ll like Contra Amatores Mundi.

9. What do you have lined up next after this novella?

Mostly teaching at the moment! But in terms of longer projects, I have a short novel in the same universe as Contra Amatores Mundi that I’m working on. I’ve written it as a sort of epistolary novel, replete with footnotes. Its working title is Those Clamorous Harbingers. I’ve some short stories in the same setting as well.

10. Why should people care about Sword & Sorcery?

To me, sword and sorcery is a genre about characters seeking freedom—they desire self-determination, and they take it for themselves (and win it for others, on occasion), despite the best efforts of gods, fate, and sorcerers. It feels like a lot of modern society (a lot of pre-modern society as well, to be fair) restricts us—tyrants of all shapes and sizes seek to control us and strip us of our innate human dignities. That all sounds rather dour, I suppose, and I don’t mean it to be.

But sword and sorcery offers an escape from those everyday tyrannies, I think.

Sword and sorcery offers a lot of other things, too. Don’t get me wrong—it can comment upon and challenge those tyrannies, too. But escape is one of its higher qualities, in my opinion. Tolkien said it better than I ever could: “Why should a man be scorned if, finding himself in prison, he tries to get out and go home? Or if, when he cannot do so, he thinks and talks about other topics than jailers and prison-walls?”

11. What was the last thing that made you laugh?

Caitlyn and I took our dogs to a nearby lake recently. Our dogs—Big Moe and Ella, respectively—are both pitbull mixes: broad chests, heads wide as dinner plates, very wrinkly around the jowl. Big Moe dipped one paw into the lake and promptly sat down on the shore, refusing all further watery engagements. Ella spent the next two hours swimming in circles, biting viciously at the waves her own paws created. This entertained her so much that she refused to leave until we waded out and coaxed her—with some encouraging words and many treats—towards the shore. It was all very silly.

We’d like to thank Graham Thomas Wilcox for taking the time to answer The Eleven Questions of DOOM!

You can find all the news about Old Moon Quarterly and other publishing endeavours on this website.

Also, be sure to check out his upcoming novella here.

We will return at the end of October with a regularly scheduled Just The Axe, Ma’am! See you then!—KB

.

Very metal! It seems there is a lot of overlap of inspirations. I too would like John Blanche (or Boris Vallejo) to do a cover for me.