Just The Axe, Ma'am #13.5 - THE ELEVEN QUESTIONS OF DOOM! with Bryn Hammond.

A monthly interview with authors of New and Notable Sword & Sorcery.

Welcome to the new launch of a feature that will serve as a companion to our monthly newsletter, Just The Axe, Ma’am!

Bryn Hammond first made a name for herself with the two-part historical novel Amgalant, based on Chinggis Khan and extrapolating from The Secret History of the Mongols.

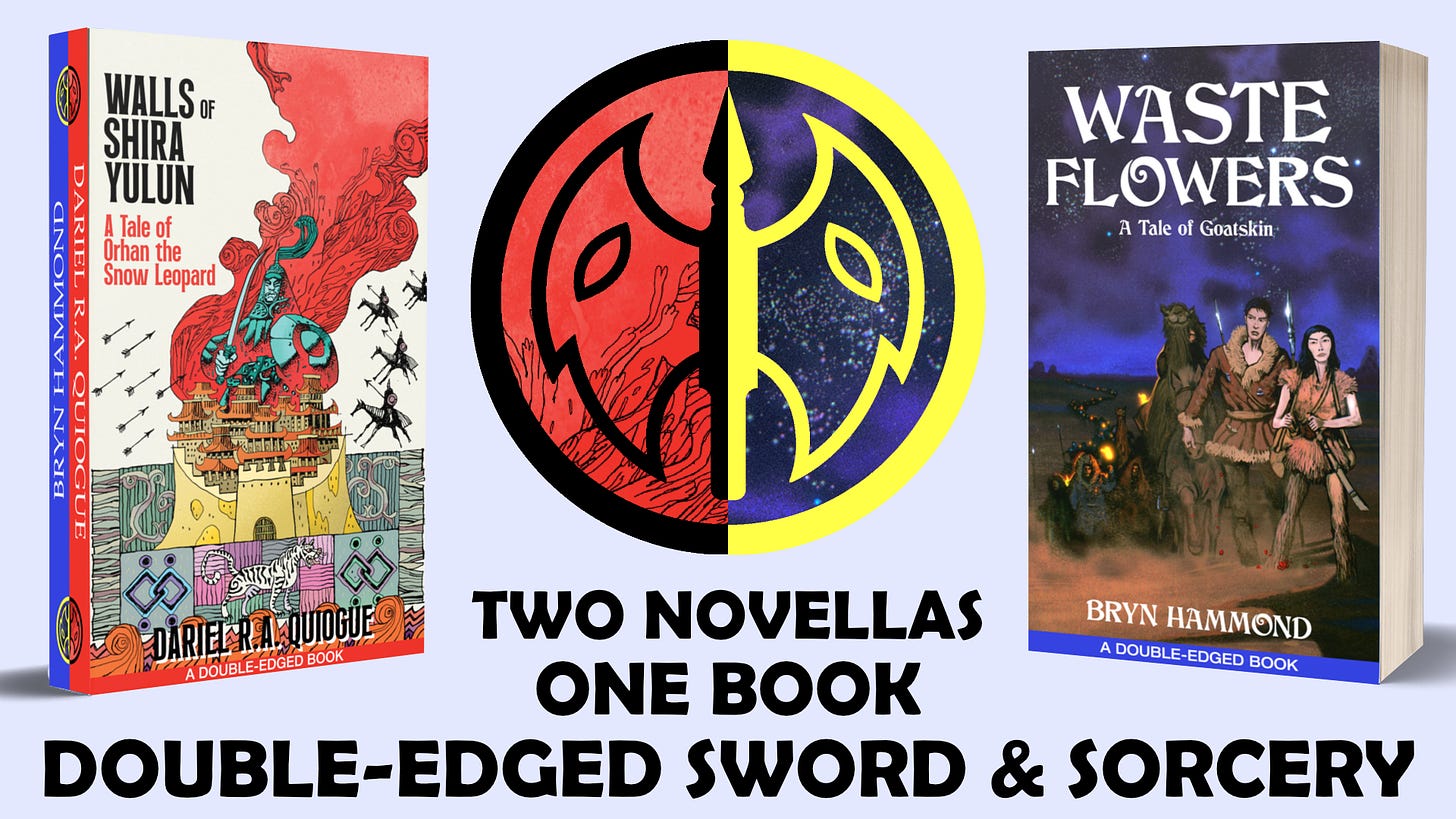

She has more recently moved into writing Mongolian-influenced Sword & Sorcery with “The Grief-Note of Vultures” in New Edge Sword & Sorcery #0, and “Sister Chaos” in New Edge Sword & Sorcery #1, and now has the novella Waste Flowers slotted as part of two books in one tribute to the Ace SF Doubles paperbacks of yore.

She discusses all this and more in the interview below, where she faces and must survive The Eleven Questions… of DOOM!

1. What was the work that made you fall in love with reading? What was the work that made you fall in love with writing? What work made you fall in love with Sword & Sorcery?

With reading? I’m going to say The Once and Future King by T.H. White. For one thing, he loves and conveys Malory, but add his acrobatics tumbling from comedy to tragedy, his British antics, his witty games with words at sentence level. He writes Nazi ants, he writes the quest for ethics, he writes Lancelot’s psychology of self-hatred and his climb to sainthood of a sort. White threw in everything he was and cared about, and then the kitchen sink.

He wrote as if nobody was listening, as if fiction mattered more than life. It did to me after that experience.

With writing? I'm not certain what you intend, but Algernon Swinburne’s Poems and Ballads (1866) addicted me to the sound of words. He gets bagged for that – more sound than sense – but in his strong work, that intoxication with language is the sail to his ship, and I have cared about how my sentences sound out loud ever since.

With Sword & Sorcery? It's hard to remember where that began. It must have been Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, or else Night’s Master and Death’s Master by Tanith Lee if those count as Sword & Sorcery. Mostly, Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser gave me a thirst for fiction that was barbarians – and lowlifes – on adventure. I picked up anything fantasy with a barbarian on the cover, although that led me to a bad place or two in the late ‘70s-’80s

2. Who are Goatskin and Sister Chaos, and why do you tell their tales?

After writing the above, I thought, oh, a barbarian and a lowlife in friendship – that’s my two. Goatskin is a nomad. To do something different after my Mongol novels, I placed her inside a settled society, where nomads are scorned and their way of life illegal. In history, nomads were often force-settled on the fringes between steppe and sown – as they are in the same places today. For my Sword & Sorcery, I didn’t want to half-arse the social contempt my hero faced.

Conan walks into a bar, everybody’s intimidated, and a lot of the men want to be him: that’s not outsidery enough for me. If Goatskin tried to walk into your average fantasy tavern or your real historical inn, she’d likely be thrown out, at least insulted. That’s the position I want to start from with my Sword & Sorcery main character. Why? I want Sword & Sorcery to get down and dirty and real with its outsider representation.

And Sister Chaos? She’s a bandit, based on a historical bandit, Yang Miaozhen. I have shifted her from North China into Tangut, where they had a bandit refuge, too, but she seizes her chances in the Mongol invasions just like Yang Miaozhen – who, as a commoner and a woman, found the chaos of the times gave her opportunity to do the otherwise impossible.

My bandit is my argument on behalf of chaos. I see fantasy metaphysics where chaos is a negative, and I ask, why? Order’s rarely on my side. Also, I come across Sword & Sorcery that takes conventional society’s attitude to bandits, and I think, what is Sword & Sorcery for if not to see the dispossessed and even anti-social point of view? My bandit bible is Eric Hobsbawm’s Bandits, and it leads to real-life accounts.

3. You have moved from meticulously researched historical fiction to writing a secondary world still inspired by medieval Mongolian culture. What have you noticed most after writing in both genres?

That effort to be meticulously researched was a feat I sustained over nine years, and I feel I’m on holiday now. I still want to talk about history, there are still things I want to tell you about historical peoples, so my Sword & Sorcery has remained strongly historical, at least in the Goatskin tales. But you can write with more symbolism, you can make your metaphors come to life as monsters, you can put things, conflicts, as physical confrontations. I’m still exploring what you can do in Sword & Sorcery.

4. You also write poetry. What do you enjoy about poetry you wish to impart to a reader?

The bulk of my poetry practice has been about oral epics or early written-down works that owe to oral epics. Epic is my first love, and the later fantastika that was called romance.

Before I abandoned the European medieval in favour of steppe epic, I spent years with Beowulf: a translation that instilled in me, indelibly, its habit of alliteration. Then, medieval Turkic and Mongol poetry works on similar structures of head-rhyme and a counterpoint syntax, and even shares a few of the ‘Heroic Age’ habits of mind.

When writing a version of the Secret History of the Mongols, I had a fine excuse to slip into poetic patches in my prose, because The Secret History slips between them. In reported speech, Mongols themselves slip into verse for emphasis, for solemnity, or for emotion. I strongly feel that those of us who write in heroic societies – probably an old-fashioned term now – ought to do justice to their oral arts.

The other thing I want to do with poetry is write settings of Mongol history, inspired by poet-historian C.P. Cavafy, who wrote a body of work on Late Antique Alexandria and its surrounds.

5. We find inspiration everywhere. What is a favourite painting, a favourite song, a favourite film?

Painting: Gustave Moreau. ‘Sappho on the Rocks’ was the cover art for my copy of Michael Moorcock’s Gloriana, and it introduced me to Moreau. The ornate, excessive, perverse iconography of his style led me into a fascination with the belated, crumbling Romanticism that was the Decadent period, its painting and writing.

Song: David Bowie. 70s. ‘Sweet Thing’ can stand for most 70s Bowie. The effort to capture ‘Sweet Thing’ in story, and convert its mood into a different medium was a constant inspiration or aspiration. Bowie’s lyrics were up there with a few poets. In that song, the ambivalence, the bizarre juxtapositions, the range and changes, were what a whole opera ought to be.

Film: I’m going to cheat and give a television series that helped teach me to write: Blake’s 7. It’s known for its antiheroes and its questioning of our crew’s actions—violence in the service of a cause—but also for putting outright space fascists on screen and locating us in the resistance. The interpersonal areas of grey just taught you to be subtle, and it was great at punchy conversations, too.

6. As someone who’s written a two-part novel about Chinggis Khan, what is one fact you wish more people knew about him?

It’d be easy to answer a question, what do people think they know, and you want to tell them it’s either untrue or unattested? There’s a lot in that category.

Fact. Facts are tricky, and almost everything is a matter of interpretation and learning how to interpret. However, I’d like people to understand that for a thirteenth-century figure, we have amazingly rich material about his insides. The Secret History of the Mongols has memoirs from people who were intimate with him and even, it seems to me, his own anecdotes. His own anecdotes – like the Secret History in general – are not self-aggrandizing, either. The concern – his concern, I argue – was to write an honest history.

I’d like people to know you can probably hear Chinggis Khan’s own voice if you listen hard to The Secret History. And you should, because it’s a world classic – as newly acknowledged by its inclusion in 2023 in Penguin Classics. Jump on it.

7. The First Wave of Sword & Sorcery is when it was formed in Weird Tales of the 1930s and 1940s. The Second Wave is when it rose high from the 1960s to the 1980s. The Third Wave is now. What is one work from each wave you want everyone to read?

First Wave. C.L. Moore, and to avoid too much controversy, I’ll say ‘The Dark Land’.

It exhibits what I like about Moore: she’s painterly, with figurative landscapes, impressionist emotions, and a language lush and stark at the same time, that draws value from repetitions like poetry or folk epic. Actually, I think ‘Black God’s Shadow’ is a gigantic masterpiece, but that takes a big screed to even talk about.

Second Wave: My weird answer to this – the toughest wave to answer on – is going to be ‘The Lamia and Lord Cromis’ by M. John Harrison. I simply love his writing, how suffused with strange moods it is, and in this late phase of the Viriconium sequence, how the story sabotages itself, but only to haunt you, to leave you in a state of disturbance because you can’t pin down the emotion you feel. That’s what a second wave ought to do.

Third Wave: At the moment, Sometime Lofty Towers is my lofty peak in contemporary Sword & Sorcery. Not that I don’t look forward to the day when it finds a rival. A rival in the revival.

That’s David C. Smith, who’s been around for ages, but like Late Yeats or Late Shakespeare, the late phase is a sting in the tail, it’s layered, it’s saturated in experience, it’s complex and disconcertingly simple.

8. You have a novella coming up in this Crowdfunder. What does it promise to the reader?

I can do one of those strings of oddments: you’ll meet the fossil bones the Gobi is famous for; camels with two humps and none; the Mongol king of the dead; ghosts of steppe-sown conflict going back a thousand years; and, of course, perturbing flowers.

Oliver Brackenbury had the fantastic idea to put me back to back with Dariel Quiogue for a Mongol Double, written by ‘steppe siblings’. You get two looks at Chinggis Khan and even two looks at his enigmatic friend-enemy, known to history as Jamuqa. Dariel cares deeply about including Forgotten Asia – Asia beyond China and Japan -- in fantasy fiction. By the end of this Double Edge, you’ll be saturated in Mongol atmosphere and mood. You’ll shut the book –both sides – and say, Huh. The Northern Thing, vaunted in fantasy circles? Not just Europe.

That’s our promise.

9. What do you have lined up next after this novella?

I’m plotting a follow-up novella, and I’ll be writing that for the next months. Working title What Rough Beast?, and wading into areas where I got my feet wet in Waste Flowers or the other Goatskin tales. Big ambitions for this one.

10. Why should people care about Sword & Sorcery?

You don’t have to care, but there’s an opportunity here for a type of fantasy you may want in your life. I especially call out to folk who are marginalized in their lives because Sword & Sorcery is shaped as a fantasy of outsiders. You don’t win kingdoms here. You don’t commonly win enough to change your life or change the world – who does? Not that we have to be pessimistic in Sword & Sorcery, but we like to stay real. It doesn’t support legitimacy or lineage, it can’t be on the side of the patriarchy though ye olde examples often didn’t see an illogic in that.

It’s anti-power in its axioms. It’s yours to come and play.

11. What was the last thing that made you laugh?

You get to hear about my own life now. Don’t forget, I learned my awkward honesty from Chinggis Khan.

Yesterday I was doing my stint at a second-hand charity shop. It’s enforced work for poverty wages, in a scheme for over-55s who’ve been out of work. Exploitative, but we muck about and laugh and have each other’s backs in a way embattled comrades of the sword should understand. So, my workmates made me laugh yesterday, but we don’t need much excuse to set us off.

I don’t try to tell them that they, too, fuel my writing of Sword & Sorcery. But they do.

We’d like to thank Bryn Hammond for taking the time to answer the The Eleven Questions of DOOM!

She may be the first, but not the last of authors who must face them!

You can find her at her website, Amgalant; if you enjoy what she had to say, check out her stories at New Edge Sword & Sorcery, and be sure to check out the upcoming crowdfunding for Double-Edged Sword & Sorcery!

We will return at the end of September with a regularly scheduled Just The Axe, Ma’am! See you then!

.

Superb!